Director’s Notes

I was participating in my third iteration of The Lark Play Development Center’s “Word Exchange,” when I came across Noé Morales Muñoz’s Hitler in my Heart. The reading, with its fresh translation by Maria Alexandria Beech, stayed with me the rest of the day. And that week. And that year. I asked for a copy of both the original Spanish and its translation, and I pitched them to every theater that would listen, every director looking for a project, and any actors simply wanting to work on a new piece. Nothing happened. Folks would read it and optimistically dismiss it as “interesting,” “smart,” or “original.” Some went so far as to call it “not exactly theater, but a staged storytelling.”

What else is theater?

This was 12 years ago.

I realize now that theatermakers, like everyone else, have their boundaries. When and how we risk requires calculation. There are stories we are ready to hear and some that we are not, and the play we call Heart of Shrapnel arrives at Elon because folks were willing to risk many uncomfortable conversations about what this work means to its community and its developing artists, the first of which was its title.

The musician Anohni, who used to identify as Antony Hegarty, recorded the song Hitler in my Heart in 1998 as Antony and the Johnsons. The song, in which a gay, male romance is first denied by one of its participants, then erased through a hate crime, ignites rage within the speaker that can only be compared to the embodiment of evil. Wanting to forgive, but finding “Hitler in [his] heart” — he finds that the full expression of that particular pain is the only thing that can redeem him:

Don’t punish me/ For wanting your love inside of me

Don’t punish me/ For wanting your love inside of me

And I find Hitler in my heart/ From the corpses flowers grow

And I find Hitler in my heart/ From the corpses flowers grow

The flowers are the song we are hearing, the art itself, the one Antony/Anohni records but also performs time and again, perhaps as a restorative ritual. The calm expressed here at the end juxtaposes the haunting, brutal first half with Anohni’s operatic vocals soaring over a nimble, blistering piano that repeats frantically as it gives way to emotive strings. The song tattoos itself to the listener, and Noé, in conversation with it, created something that similarly tattooed itself to me.

The work of translating never finishes. The printed text is only an approximation. Our artistic team asked (and still asks) itself hundreds of questions about society, sports, violence, interpreting notions of so-called class, privilige, race, sex, religion, and immigration in order to get at something that approaches Noé and Maria Alexandria’s voices about their worlds. Ultimately, we agreed; we will not be able to interpret anything unless our play exists in the liminal spaces between the United States, Mexico, and beyond — in a city that is neither Monterrrey nor Seattle, but a globalized city, in the globalized world.

Make no mistake, the main concerns of this play come from a Mexican perspective about American culture. Our particular brand of commerce, fueled by iconography, cinematography and the use of idolatry through celebrity are squarely in focus here, and if fútbol is the second act’s subject, it is only because it is the sport that the world knows, the one that our playwright could speak in. Trade tethers some 7.6 billion people across the globe, and marketing it requires a particular kind of myth-making that feels omnipresent, working its way into our conversations, thoughts, doubts, aspirations, evaluations, and determinations. True to Noé’s vision, we want to free the audience of those burdens by magnifying and exploding those myths.

We began crafting this production, this particular tattoo, with you in mind, with the idea that the people experiencing it should receive something that cannot be obtained anywhere else because nowhere else would have it, and that must point to something. This means that the new ‘we’ (the production team with the audience, together) is both privileged and ostracized, peddlers as well as believers, institutional peons as well as blue-collar survivors. We are, in other words, the characters in this play. And isn’t that what theater, or “staged storytelling,” is all about?

Thank you for reading this.

Thank you for being here.

Thank you, Elon and Central NC, for participating with your entire imagination, in something beyond the transaction, wrestling to find a language we can all speak in.

Special Thanks

Dr. Connie Book, Dr. Aswani Volety, Dr. Gabie Smith, Chair Lauren Kearns, Kim Shively, Fred Rubeck, Alfredo de Quesada, Andrea Thome, Hathaway Pendergrass, Kirby Wahl, Bret Sherman, Kenny Harvey, and Dominika Beza Handzlik

Cast

| A | Briston Whitt |

| B | Taylor Ann Mitchell |

| C | Payton Robinson |

| X or Y | John Lee Rudolph |

| X or Y | Alec Wilson |

| Clerk | Callie Fabac |

| Cop | Eduardo Sanchez |

| Understudies | Alyssa Wise, Conrad Hall, Delaney Lynch, Manu Cornick Fernandez, Niklas Salah, Sarah Cadol, Sean Mikesh |

Production Team

| Director | Andres Munar |

| Scenic Designer | Elizabeth Brady |

| Costume Designer | Caitlin Duncan |

| Sound Designer | Michael Smith |

| Lighting Designer | Alex Nemfakos |

| Technical Director | JP Mullican |

| Stage Manager | Peyton Otis |

| Assistant Stage Manager | Sarah Adams |

| Production Manager | Bill Webb |

| Costume Shop Manager | Heidi Jo Scheimer |

| Props Coordinator | Natalie Hart |

| Sound Board Op | Sydney Bell |

| Props Crew | Sage Harris |

| Deck Crew | Kayla Jordan |

| Front-of-House Supervisor | David McGraw |

| House Manager | Keri Anderson, Ella Huestis, Laura McGuire |

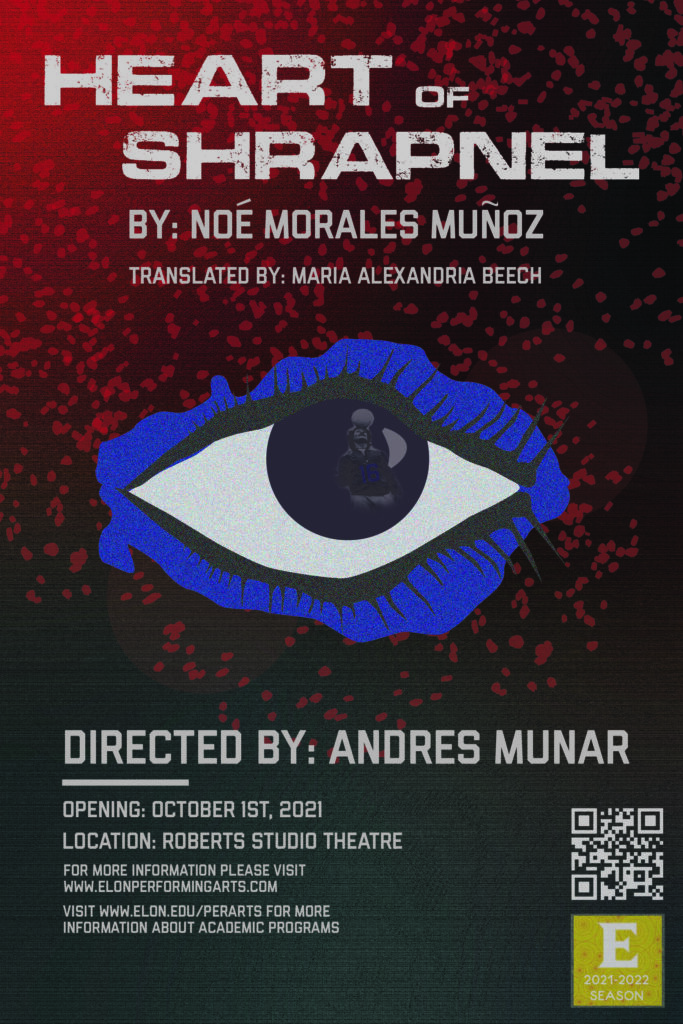

| Poster Design | Sydney Dye |

Bios